His lyrical, conceptual approach to designing public spaces leaves a colourful and deeply original imprint on North American cities.

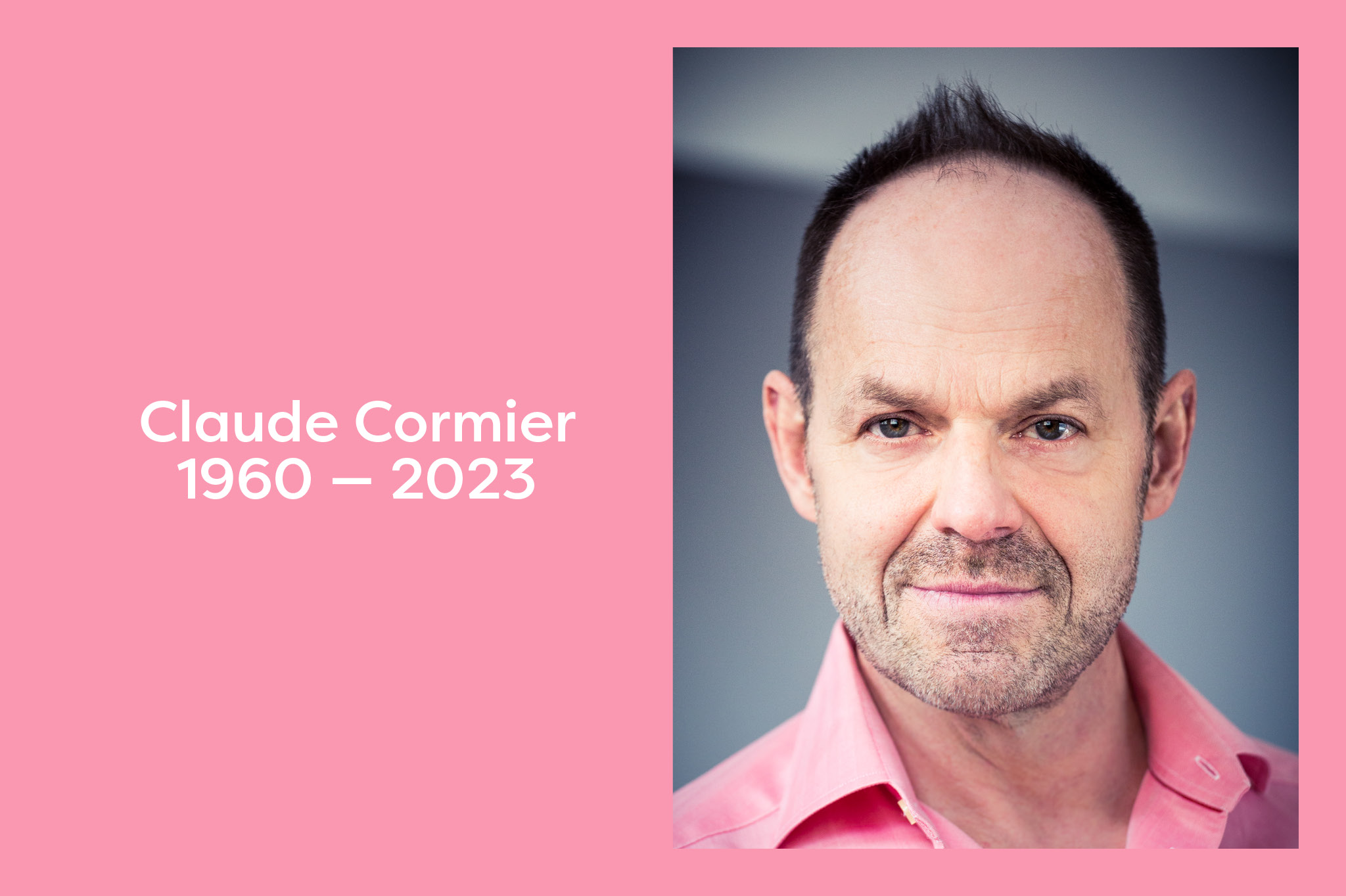

Landscape architect Claude Cormier, the creative force behind of some of Canada’s most beloved, joyous, and critically acclaimed public spaces, has died at his Montreal, Quebec, home on September TK. He was 63. The cause of death was complications from Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, a rare genetic condition that predisposes carriers to multiple cancers.

Cormier’s joyful and subversive designs blended conceptual clarity with a studied instinct for making enduring places. His ability to design public spaces with broad public appeal stemmed from multiple qualities: audacity, sincerity, discipline, leadership, business acumen, a talent for creative problem solving, and an ability to bring light and laughter to everyone—and every situation—he encountered.

Along with being a gifted designer, Cormier was a deft strategist and salesman who knew how to win over even the most status-quo-minded municipal bureaucracies. For Toronto’s Berczy Park (2017), he proposed a prominent water fountain featuring life-sized bronze dogs (and a single cat); officials told him that “dogs were not art.” In response, Cormier’s team put together a 50-page presentation on the role of dogs in art over the last 500 years. This paved the way for one of Toronto’s most beloved parks for humans and dogs alike.

Cormier’s love of fashion often translated into project pitches where his team would dress up to embody a project. They appeared in full camouflage for early design workshops on Camouflage Park (concept, 2003) in Toronto. For a public presentation on the revitalization of Place d’Armes in Montreal (concept, 2007), the square in front of the towering spires of the iconic Basilica Notre-Dame, they donned hardhats embellished with an antler-like rack of crosses. More recently, Cormier memorably wore Rick Owens platform boots to spark humour and surprise—as well as to “boost his stature”—at the announcement of his $500,000 donation to establish the Claude Cormier Award in Landscape Architecture at the University of Toronto.

Cormier came from modest, hard-working rural roots, growing up on a farm and sugarbush near the small town of Princeville, Quebec. He was the eldest of two boys and third of four children. Cormier’s father, Laurent, was a farmer; his mother, Solange, was a teacher. Cormier embarked on an education in agronomy and plant genetics at Laval University in Quebec, with the intent of taking over the family farm. After his father died in 1976, when Claude was 17, he re-directed his education—first to finish his undergraduate degree in Agronomy at the University of Guelph in 1982, and then to study at the University of Toronto, where he graduated in with a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture in 1986. Cormier then sought out Phyllis Lambert as a benefactor: Lambert agreed to finance a year at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 1994 for Cormier to obtain a Master’s degree in the History and Theory of Design, in exchange for Cormier’s commitment to consult on the landscape stewardship of Lambert’s recently built Canadian Centre for Architecture.

At Harvard, Cormier was influenced by the theories of landscape architects Martha Schwartz and Peter Walker, whose exploration of the artistic and conceptual potential of landscape design were a departure from the modernist orthodoxy of the previous generation. Cormier often described himself in lectures as the illegitimate love child of Schwartz and his other major influence, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the iconic designer of New York City’s Central Park and Montreal’s Mount Royal Park, who Claude admired for his broad social vision and shared affinity as a “scientific farmer.”

Setting up practice in Montreal in 1993, Cormier’s early installation works established a reputation for projects that incorporated abstraction, storytelling, conceptual art, and the bold use of colour. This stood in sharp contrast to the traditional landscape palette of plants and pavers. His first commission, Enchanted Forest (1993), was a temporary installation in Bar Le Business, Montreal’s answer to Studio 54, where a forest of real trees provided the mise-en-scène for the narrative of Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf to play out on the dance floor. The Blue Stick Garden at the inaugural Métis Garden Festival (1999) was composed of painted sticks inspired by the classic Victorian border garden, with a gradation of heights from low in the front to tall in the back. The sticks were coloured with the intense hues of the Himalayan Blue Poppy, the site’s signature flower. The garden made a splash as a bold and controversial installation, which to visitors felt like a conceptual artwork masquerading as a garden. Ideas from this period became through-lines in Cormier’s work, and were captured in a 2008 manifesto, with maxims including: “A Garden is About Experience, Not Plants,” “Colour is not a Decoration,” “Artificial but not Fake,” and 32 others; ten more were added later.

Cormier’s work quickly scaled up to include public spaces in Montreal and his second adopted city, Toronto. His design approach favoured singular design ideas imbued with humour and grounded in a deep understanding of human social behaviour—including the theatrical way people use public space to see and to be seen.

In Montreal, Cormier’s signature projects reveled in the tension between history and contemporary design. His first competition-winning project in the city he made his home was Place d’Youville (Phase 1, 2002; Phase 2, 2008), a tree-filled linear plaza in the Old Port, crisscrossed by paths connecting the doorways of adjoining buildings. His vision for rejuvenating Dorchester Square (2010) incorporates mannered riffs on Victorian elements, including an ornate multi-tiered fountain sliced in half vertically (the flat end truncated to make way for a bus route). His best-known contribution to Montreal’s historic waterfront is Clock Tower Beach (2012) with its distinctive blue umbrellas.

Toronto’s waterfront is home to three international competition-winning Cormier landscapes. Completed in 2007, HTO, designed in association with Janet Rosenberg Associates, was the first in what would become a series of urban beaches designed by Cormier. Sugar Beach (2010) riffed on the beach theme, but this time with giant candy-striped rocks and “Jackie O”-pink umbrellas. His design for Leslie Lookout Park, currently finishing construction in Toronto’s Port Lands, creates a new connection to a shipping channel with a beach, forested dunes and a lookout tower. Cormier’s ability to think three-dimensionally and at large scale made him an invaluable contributor to projects such as The Well in Toronto, expected to open this November, where the high-quality granite materials of the multi-level ground plane and serene linear gardens set the tone for a retail, office and residential development that covers nearly an entire downtown block.

Several projects showcase Cormier’s role as a design ambassador for queer issues. In these projects, Cormier’s characteristic blend of avant-garde techniques and accessible fun create places that emotionally resonate with—and beyond—LGBTQ2S+ clients and communities. Whether conveyed through the pink columns of Lipstick Forest (2002), Sugar Beach’s signature pink umbrellas near the base of Toronto’s Gay Village, or the rainbow balls of Cormier’s brilliant Pink Balls (2011-2016) and 18 Shades of Gay (2017-2019) installations that hung over Montreal’s Sainte-Catherine Street East every summer for nearly a decade, the expression of queer joy was an important dimension of Cormier’s design identity.

Cormier’s impact as a mentor of students and employees featured prominently in the recent outpouring of love from those whose lives he touched. One landscape student from the mid-1990s remembered Claude’s inspiring conversation about a “crazy doughnut scheme” the student had come up with. The then-student recalled that “we chatted […] not about the doughnut, but the hole in the doughnut that allowed it to express its doughnutness. It was a comedic chat, but at the same time very serious. That conversation allowed me to see another angle of a design proposal—and also the power of whimsy.”

Cormier’s last major works are love letters to his two chosen cities, Montreal and Toronto. The Ring in Montreal (2022) is a monumental 30-metre-diameter steel hoop, suspended between the modernist towers of Henry Cobb’s 1950s Place Ville Marie. As a piece of visual poetry, the installation marries the beloved mountain and the revitalized public space of the downtown office complex. Love Park in Toronto (2023), a heart-shaped pond enclosed by a 170-metre-long red mosaic “love seat,” transforms a former freeway offramp into a town square for a growing community on the city’s downtown waterfront. The late part of his career also saw the publication of a major retrospective called Serious Fun: The Landscapes of Claude Cormier by Marc Treib and Susan Herrington (ORO Editions, 2021), and the rebranding of his 15-person office to become CCxA, marking the passing of the torch to long-time collaborators Sophie Beaudoin, Marc Hallé, Guillaume Paradis and Yannick Roberge.

In August 2023, Cormier was videotaped for a forthcoming oral history by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), part of the Pioneers Oral History series that features significant landscape architects. TCLF President and CEO Charles A. Birnbaum notes, “Cormier’s design approach is unique in the landscape field—his work pulverizes the notion that history and design can’t be happily wed. He consistently designs projects that are original, fresh, memorable, painstakingly detailed, and revel in being both highbrow and lowbrow.”

The quality of the work by Cormier and his team has garnered the highest honours of the landscape profession, including more than 100 awards. These include recognition from publications such as Fast Company, Azure and Canadian Architect, and organizations including the Canadian and American Societies of Landscape Architects, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, and American Institute of Architects. Cormier is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and Knight of the Ordre National du Québec. He has received individual and lifetime awards from the Association des architectes paysagistes du Québec and Architectural League of New York.

Many of Cormier’s best-known spaces were the result of winning national and international design competitions, often in collaboration with renowned Canadian and international architects. When he initially turned down Daniel Libeskind’s request to collaborate on the Ottawa Holocaust Memorial because he thought he had little to offer, Libeskind called back to explain, “I can bring the darkness, you bring the light,” which ultimately became the underlying idea of their competition-winning design. Perhaps bringing lightness to the art and science of landscape is a fitting metaphor for Cormier’s design legacy.

Four years ago, Cormier was diagnosed with lung cancer, kidney cancer, and a rare form of lymphoma. Cancer had prematurely taken the life of his sister Raymonde at the age of 53 in 2009, his father Laurent in 1976, and the lives of nearly all his aunts and uncles on his father’s side. His triple diagnosis led to an investigation into possible genetic origins, and the devastating realization that a branch of his French-Canadian family tree was affected with the genetic mutation known as Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, whose carriers have an increased chance of developing cancer. In the face of this knowledge, Cormier worked with a biomedical researcher on open communication, genetic testing and education tools that could inform and protect his own family and others facing similar diagnoses. He approached this difficult communication challenge with the same spirit of openness and generosity that characterized his creative career.

Claude Cormier leaves behind an incredibly wide circle of friends, including Ian MacKay, Liette Locas, Martin Roy, Chris Farnet, Maxim DeNobrega, Philippe Lebel, David Platts, Jennifer Luce, Michele Boisvert and Marc Jutras. He is survived by his mother Solange, sister Louise, brother Pierre, nieces Marie-Laure, Delphine, and Léa-Sam, and nephew Alexis. He also leaves behind his CCxA work family including Sophie Beaudoin, Marc Hallé, Guillaume Paradis and Yannick Roberge.

Written by Beth Kapusta